Hydroelectric Power from the Clyde

Hydroelectric power in Scotland is normally associated with the Highlands and with lochs and mountains. It may come as a surprise that there are hydroelectric power stations on the Clyde, dating back to 1927, in areas not associated with mountains.

The Clyde has its source in the Southern Uplands at Watermeetings where it is formed from the confluence of two streams and, heading north, it forms a valley which is used now as a cutting for the M74. At Abington, the Clyde and the Motorway part company and the river flows towards Lanark where it descends in a gorge with dramatic waterfalls through the Clyde Valley towards Hamilton/Motherwell and then on to Glasgow. It is only the region downstream from Glasgow that is really navigable. In other regions, there are rocks and rapids and only short stretches can be navigated.

The Falls of Clyde

The falls around Lanark are known collectively as the Falls of Clyde. The biggest waterfalls are upstream from New Lanark, Corra Linn (Pictures below) and Bonnington Linn.

Corra Linn in full spate. Date of photo: 15th September 2006

Corra Linn. Date of photo: August 2006

Cora Linn is the most spectacular and can be seen easily from a footpath heading out of New Lanark.

Bonnington Weir

This is the first part of the Lanark Hydroelectric Scheme. The weir controls water diverted from above Bonnington Linn through pipes to Bonnington Power Station.

Bonnington Weir. Date of photo: 9th September 2009

Sluice gates diverting water. Date of photo: 9th September 2009

The brown bucket is part of an automated system to remove debris collected on the filtration grid.

View above sluice gates at Bonnington Weir, showing Clyde upstream. Date of photo: 9th September 2009

Plaque on sluice gates at Bonnington Weir. Date of photo: 9th September 2009

The weir gate has a plate which shows it was built by Ransomes and Rapier, Ipswich, England in 1925 (see footnote)

Bonnington Iron Bridge. Date of photo: 9th September 2009

A nearby old cast iron bridge spanned the Clyde from the east bank of the river to an island overlooking Bonnington Linn.

Bonnington Iron Bridge - explanatory notice. Date of photo: 9th September 2009

Bonnington Power Station

Bonnington Power Station. Date of photo: 24th October 2006

Water diverted from Bonnington Weir is diverted through pipes to Bonnington Power Station that can generate 11 MW from its turbines. The pipes to the Power Station were relaid in 2006.

Relaying pipes to Bonnington Power Station. Date of photo: 24th October 2006

Stonebyres Power Station and Weir

Further downstream, beyond Kirkfieldbank is a smaller waterfall, Stonebyres Linn, which is used to supply Stonebyres Power Station. This station can produce 6.4 MW.

Both Bonnington and Stonebyres Power Stations are automated and controlled by engineers at Stonebyres.

Stonebyres Power Station. Date of photo: 24th August 2009

The two Francis turbines in the turbine hall at Stonebyres. Date of photo: 24th August 2009

The elegant windows inside Stonebyres with a view through of the green inlet tube. Date of photo: 24th August 2009

Part of the original control panel at Stonebyres (the clock does not look original!). Date of photo: 24th August 2009

I am grateful to Scottish Power for permission to photograph inside Stonebyres Power Station

Upstream, Stonebyres Weir diverts the water from the Clyde through pipes down to The Power Station. The weir can be easily reached from Kirkfieldbank.

Weir across Clyde at Stonebyres. Date of photo: 21st July 2007

Plaque on weir gates at Stonebyres. Date of photo: 21st July 2007

As at Bonnington Weir, the weir gate has a plate which shows it was built by Ransomes and Rapier, Ipswich, England in 1925 (see footnote)./

Stonebyres Weir - weir gates on left and coarse filtration plant straight ahead. Date of photo: 5th August 2009

Part of Stonebyres Linn- photo taken from weir gates. Date of photo: 21st July 2007

Stonebyres Linn is difficult to photograph. Its steepest falls can be partially seen from the Clyde Walkway, but the view is obscured by the trees

In 2008, Scottish Power committed to a two-year upgrade programme to ensure the future of the Lanark Hydro scheme, but this was later sold in 2019 as part of a restructuring of Scottish Power. Drax became the owners of the Lanark Hydroelectric Scheme and in June 2020 announced the completion of a a £1.1 million investment to rejuvenate Stonebyres Power Station while retaining its original features.

New Lanark Mills

The New Lanark Mills

The cotton mills in New Lanark were built in the late 18th century by David Dale to take advantage of the water power available from the Clyde. A weir built above Dundaff Linn, the smallest of the Falls of Clyde, retained water to divert it through a tunnel to a lade built at the back of the mills. Each of the four mills had its own waterwheel (or waterwheels) built underneath to take water from the lade and discharge it into a tail-race, which fed the water back into the Clyde. The waterwheel drove a vertical driveshaft through bevel gears. At each floor, a horizontal drive shaft took power from the main shaft through bevel gears. Waterwheels were troublesome and from 1886 onwards, there began a series of developments with turbines which eventually replaced all the waterwheels. In 1898, a dynamo was attached to one of the turbines to produce electricity for lighting the mills and the village houses. The power output was feeble and, as electrical appliances such as radios and irons became available, the demand for power could not be met and led to frequent blowing of fuses. In 1955, the decision was made to link the village housing to the public mains supply. At about the same time, individual electric motors were fitted to the mill machines and were powered by the output from induction generators coupled to the turbines.

Dundaff Linn, the smallest of the Falls of Clyde

The calm water above the weir before Dundaff Linn and the sluice gates taking water into the Mills system

The Mill Lade, with the water entering the site through the tunnel

L to R, the water wheel on the site of the former Mill Four, the School and the Dyeworks

The Mills and Lade

The sluice gates controlling the flow of water into the turbine

In the restoration of the mills, the New Lanark Trust used the remaining water turbine to generate electrical power. This, a Swedish-built Boving turbine installed in Mill Three in 1931, was coupled to a modern induction generator to produce up to 380kw of electricity per hour to supply most of the needs of the New Lanark Mill Hotel and Visitor Centre. Any surplus is exported back into the grid. The power also drives the 19th century spinning mule, not only for demonstration to visitors, but also for the commercial production of high quality woollen yarn, mainly for home knitting.

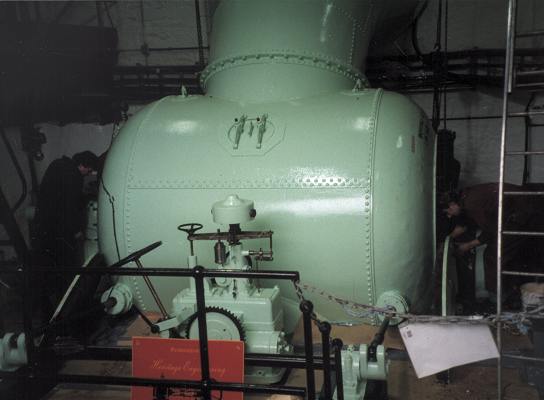

The Boving Turbine under Mill Three

End view of the Boving Turbine

The panel controlling the water system and the turbine

The visual interface for control

The Trust has extended its use of sustainable energy by using two heat pump systems to extract heat from the water. One uses heat-exchange plates fixed to the wall of the lade to heat the Institute and the other takes heat from the wheel-race under Mill Two to heat the Hotel swimming pool and leisure suite.

Heat pump installed in the basement of Mill Two

If you have not visited New Lanark, you should. The village and industrial buildings have been beautifully restored. An exhibition shows the history of the mills, the village and the workers. It details the remarkable social reforms implemented by Robert Owen, who took over management of the mills from his father-in-law, David Dale. New Lanark is now an UNESCO World Heritage Site. From here, you can also explore the natural beauty of the Falls of Clyde Wildlife Reserve.

The Bell Tower in the main street of New Lanark (through the Rose Garden)

I am very grateful to Lorna Davidson, Director of the New Lanark Trust and John Marshall, Property Manager for supplying information and for the photograph of the Boving turbine. In July 2010, John very kindly showed my wife and myself round the hydroelectric power and heat pump installations which he was instrumental in developing.

Since that time, Lorna Davidson has retired from the New Lanark Trust and John Marshall has moved to another appointment.

Blantyre Weir

Blantyre weir with small hydroelectric station

In 1995, a small hydroelectric plant was built to take advantage of the head of water at an existing weir at Blantyre, further towards Glasgow. The single turbine is capable of producing 575 KW.

It was operated by RWE Npower Renewables Limited when I first wrote this article. The company was later taken over by Innogy who featured Blantyre on their website. Now Innogy has been taken over by E.ON who have no mention of the Blantyre site on their website. I currently am not able to confirm who the current owners are or whether the scheme is still operational.

Further Information

- The Lanark Hydroelectric Scheme - Wikipedia

- Drax acquires Lanark Hydro Scheme as part of £702m power deal

- Bonnington Power Station on Google Maps

- Foot Bridge, Bonnington Linn

- Stonebyres Power Station on Google Maps

- £1.1m refurbishment of historic Drax hydro power station at Stonebyres

- Clyde Walkway around Falls of Clyde

- Ransomes and Rapier - Wikipedia

- Brackett Green trash rakes for coarse filtration

- Fixing the feeders (Bonnington and Stonebyres)

- New Lanark World Heritage Site

- New Lanark Power Trail, Lorna Davidson, New Lanark Conservation Trust, 2006. Available from various booksellers

Footnote - Engineering in Ipswich

It is perhaps unexpected that Ipswich, the largest town in the largely agricultural county of Suffolk, was an important centre of engineering. It developed out of a need for agricultural machinery. The foundry of Ransomes was formed in 1789 to produce ploughshares. This developed later to include the manufacture of traction engines, threshers and lawnmowers.

In 1869, the company split to create an offshoot, Ransomes and Rapier, to concentrate on heavy engineering - railway turntables, railway cranes, dockside cranes, mobile cranes and sluice gates. Its most famous product was a huge electrically-powered walking dragline, which, at the time it was built (1951), was the largest in the world.

Engineering in Ipswich also attracted an American firm, Crane Ltd to build a large factory to produce valves, radiators and fittings. There were also smaller foundries in Ipswich. Sadly engineering in Ipswich has been is serious decline and, in 2008, the last remaining engineering employer, Crane Ltd, sold its site and moved production to Hitchin and China.

My interest in this subject is that I was born in Ipswich and my father, uncle and cousin all worked in the engineering industries there.